The legendary Chenghua ‘Chicken cups’ are more than just artefacts; they are windows into a once tangible world. Only four remain, ensconced within the halls of museums like the British Museum and the Victoria and Albert (V&A) Museum. Each artefact, including these cups, carries with it whispers of a bygone era – the conversations, the craftsmanship, the rhythms of daily life. These artefacts serve as essential links, especially in an age where history and culture are far more malleable, open to manipulation, distortion, or even erasure. They remind us that while no single individual can recount the entirety of a nation’s past, objects offer silent testimonies to moments that shaped civilisations.

Yet, in the vast narrative of China, there exists an anomaly. There’s a generation alive today that has traversed through China’s most transformative period. They’ve not only witnessed but lived the entire modern history of their nation. Their stories are not just tales; they are firsthand accounts. It’s a unique phenomenon where the breadth of a nation’s monumental journey can be encapsulated within a single lifetime.

This realisation struck me profoundly during my first trip to China at 17. What started as a lunchtime extracurricular to boost my unsuccessful Cambridge application in a class of around twenty quickly turned into a transformative experience. Along with two classmates, I embarked on a trip to China, driven by curiosity that far surpassed any language skills we possessed. Arriving in China, the country was nothing like my presumptions, which were largely formed by outdated information. Contrary to expectations of an oppressive police state or underdeveloped nation, I found a modern, wealthy society. Yet, as a teenager from Harrogate, the skyscrapers and luxury of Shanghai left an indelible impression, justifying multiple return visits.

As nations globally pivoted towards industrialisation, shedding the shackles of monarchies and serfdoms, China too found itself at the cusp of metamorphosis. The seismic shifts in the West, illustrated by events in France and Russia, were not lost on China. Their hunger for change culminated in the Chinese Civil War from 1927 to 1949. With the ascension of the Communist Party of China (CPC) in 1949, a nation was reborn. Projects like the first Five-Year Plan in 1953 and the Great Leap Forward in 1958 marked China’s relentless march towards a modern identity. But the path was fraught with perils. Mao’s ambition saw the rise and fall of many, eventually paving the way for one of history’s most tumultuous eras: the Cultural Revolution.

This period stands apart in China’s history. Unlike other major revolutions which simply sought to break ties with the past, the Cultural Revolution aimed to forcibly erase remnants of China’s historical and cultural legacy. Numerous physical symbols associated with China’s long history and cultural heritage were targeted and destroyed in an effort to eliminate “the Four Olds” – old customs, old culture, old habits, and old ideas. Many religious and cultural sights were destroyed or repurposed, traditional clothing, like the qipao and the changshan, was discouraged or forbidden, replaced by the more utilitarian Mao suit. The bearers too were targeted, anything seen as representing feudal or bourgeois elements was at risk. Many academics, intellectuals, and even students in urban areas were sent to live and work in agrarian areas to be re-educated by the peasantry and to better understand the role of manual agrarian labor in Chinese society.

From this turbulent period emerged a blank slate. This canvas, painted in the blood of sacrifices—sacrifices to the party, of knowledge, individuality, and aspirations—all sought to serve the vision of common prosperity. Amidst this backdrop of intense ideological warfare, China sought a fundamental redefinition of its identity. To an extent, there was no need for history as those living through the Cultural Revolution were actively crafting it—pulling a fractured nation overlooked by the world from the dust and reimagining it as a phoenix. What had taken centuries to develop across the Western world was achieved in China within just a few decades. This era wasn’t just about political change; it was about redefining what it meant to be Chinese.

The generations that followed have grown up witnessing a modern, powerful China. Skyscrapers, high-speed trains, and digital innovations dominate the skyline, emblematic of a rejuvenated China that has “stood up” to the world, largely due to the sacrifices borne by their predecessors. However, the echoes of deep-rooted traditions, which provided a coherent sense of identity for millennia, have faded in many areas. Walking through the streets of Beijing, Shanghai, or Shenzhen reveals hubs of modernity. But many of the traditional hútòngs (alleys) and siheyuan (courtyards) that once epitomised Chinese urban life have been replaced by commercial complexes and towering high-rises, markers of China’s swift urban metamorphosis.

But when what defined this metamorphosis has been eroded by COVID, a housing bubble, and rising global tensions, fracturing the facade which had first drew me in to reveal the deeper complexities of a nation grappling with its own cultural identity. As I sought a more genuine experience of the countries culture, travelling first through Guizhou, Chengdu and finally through Dunhuang and the north west, I saw a vast dissonance, not only from my own prior experience but from those nationals who travel within their own country with a sense of novelty and detachment.

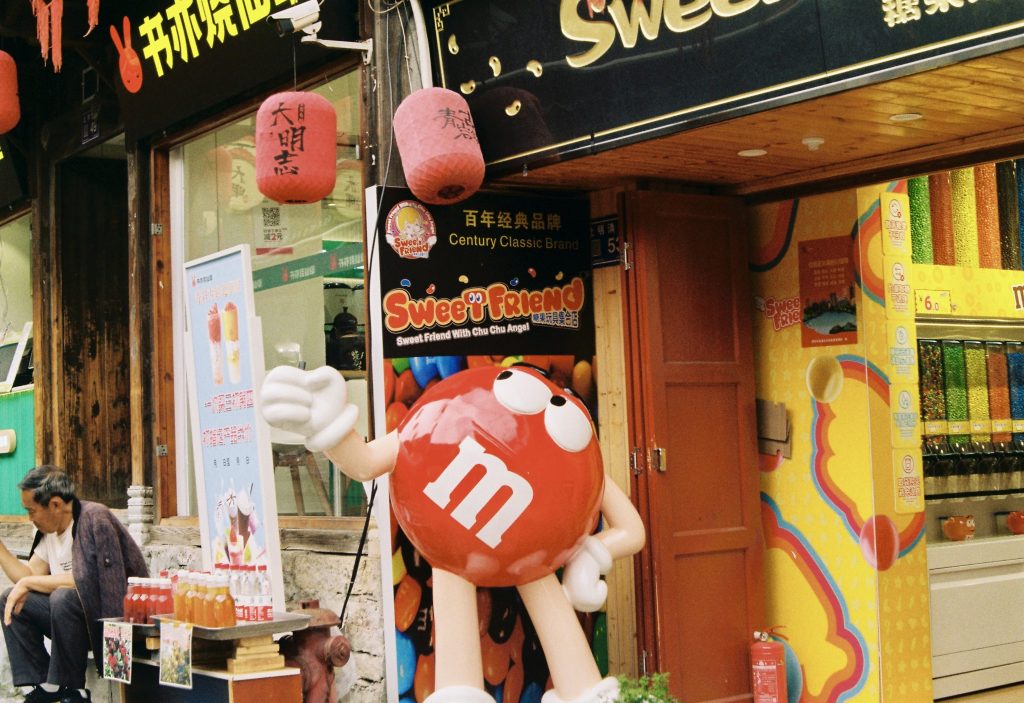

The historical sites I visited, repackaged and commercialised, often fail to offer genuine insights into the nation’s past. Supposedly ancient temples, which were as new and serving as nothing more than backdrops for photos. The roofs of ancient villages serving only to cover streets covered in hundreds of gift shops. The new not so seamless blending of the new into the old. And at each, you would find admission booths, bubble tea, and sausages, likely more ancient than the architecture itself, rotating around waiting for patrons who made their way up from the many cable cars and paved pathways.

Even heritage sites are seemingly muddled, Song Peilun, a former professor turned artist has finally finished his vision of paradise based on colorful minority cultures based in southwest China’s Guizhou province. Only which culture remains ambiguous, it seemingly never existed and its nothing more than a confused amalgamation.

This has only been accelerated by President Xi Jinping’s concerted effort to reinforce party-centric narratives and a specific version of national identity. This state-sponsored vision of history does more than just whitewash certain events; it actively seeks to realign cultural memory. The distortion of historical events or characters to fit contemporary political narratives isn’t just about censorship. It’s a proactive move to restructure the collective memory of the nation. For instance, the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests are not part of the public discourse, with the events largely hidden from the younger generation.

Historical narratives are not just overlooked; they are actively reshaped. The show at the Château des ducs de Bretagne history museum was planned to open in February 2021. But following a series of proposed interventions by Beijing authorities, the museum has decided to postpone until at least 2024. The interference was the result of “a hardening of the Chinese government’s stance this summer against the nation’s Mongolian minority,” the museum’s director Bertrand Guillet said in a statement. Attempts at censorship first began as an injunction from CCP authorities to remove the words “Genghis Khan”, “empire” and “Mongol” from the entire show, which was being organized in collaboration with the Inner Mongolia Museum in Hohhot, China. Chinese authorities demanded “control of the exhibition’s production”, which included providing a new exhibition synopsis written by the National Administration of Cultural Heritage in Beijing.

The emphasis on traditional Chinese values, the revival of Confucianism in the public discourse, and the push towards a more “Chinese” way of life suggest an attempt to bridge this chasm. However, the top-down approach, where traditions are “reintroduced” rather than organically revived, runs the risk of further alienating citizens. Notably, a TV series attempting to reconcile Confucianism and Marxism, ending in a rather overt threat over Chinese interest in Taiwan, was received with little enthusiasm. Simultaneously the Xi-centric state demands more of the same sacrifice as he himself offered. This time it is been rested (lying flat). Perhaps these minds wonder what life used to be like, if there is an alternative? But the answer to that question has long been lost.

Writing this article I do feel a great sense of pity, when I first returned from that summer trip I advocated for a country that offered so much more than how it was been portrayed, a nation which emerged and grew faster than any other and was beginning to establish a new foothold within the modern world. But after COVID it seems insecurity over the economy and political leadership has dislodged this and in its place a manufactured culture slowly takes root, one which resembles the same misguided perceptions which I had initially